Many thanks to Tony Vega of the Japan Station podcast for welcoming me back! Listen to the interview on Apple Podcasts or in your browser, and follow along with the transcript below (edited for clarity).

TONY VEGA: My guest today is Charles Kowalski, and he’s actually a returning guest. He was on the show back in episode 20. So that was four or five years ago, back in 2019. So it’s been a long, long time, but Charles is a writer, he’s a teacher living in Japan, and he’s the author of the Simon Grey series of books. These are really, really fun books. They are targeted at a younger age, like young adult, but they are just really well written. They’re really enjoyable even if you’re a bit older. The first book, Simon Grey and the March of a Hundred Ghosts, is mainly about yokai and ghosts, and it’s a really, really fun book. I still remember it, I read it before the interview, and now he’s got a new one coming out, Part 2 of this series, Simon Grey and the Curse of the Dragon God.

I really enjoyed this book. I’m not going to get into all the details, but there there’s some really fun historical and supernatural stuff in this book. It’s coming out in early October, so it may be out by the time that you’re listening to this. It’s available on Amazon and probably wherever else you get your books, just do a quick search online or you can find it over at simongreybooks.com. So I’m not gonna go on and on and on. Just know that this is a fun conversation. We get into supernatural stuff, yokai stuff, historical stuff with hidden Christians in Nagasaki and the famous Shimabara Rebellion, which maybe you’ve heard of, but like me, you don’t know all the details. We’re getting into that because Charles did a lot of research for all that. So here we go. Here is my conversation with Charles Kowalski.

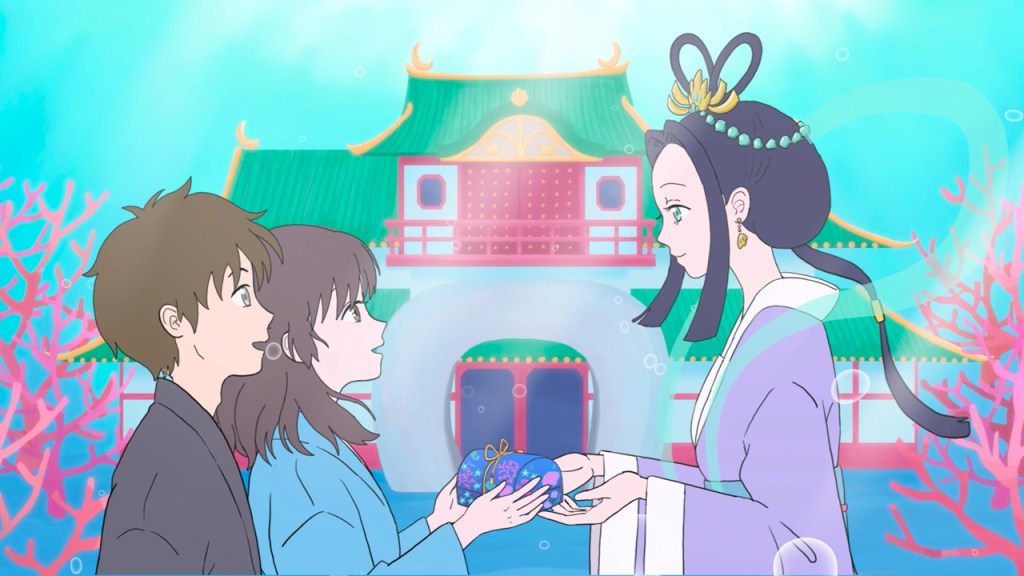

The inciting incident, so to speak, is this whole Urashima Taro related thing with the castle and Otohime and going under the sea and all that. I think people that listen to the show are familiar with Urashima Taro. But then the characters end up during this thing called the Shimabara Rebellion. I’ve heard of this, and probably saw some entries on Wikipedia or something before, but I never really looked that deeply into it. Could you tell us about what this is, what’s so interesting about it, and what led you to focus in on this specific time in Japanese history?

CHARLES KOWALSKI: Well, let me start from the end. Let me start from the last of your questions, because as we discussed last time, I was really intrigued by the story of Urashima Taro, and I wanted Simon and Oyuki to follow in the footsteps of Urashima Taro when they pay a visit to Ryugujo. And they don’t stay quite as long as Urashima Taro did, but still, when they come back to Japan, they find that a number of years have passed in the interim. They are now stranded in Japan and it’s now during what’s known as the sakoku jidai, the time when the country was closed, and for any foreigner or half-blood to be caught on the mainland was a crime. So that was the idea that I started with. And so I didn’t set out actually to write a story about the Shimabara Rebellion, I just took that starting idea and thought, “OK, well, where do I go from here? Did anything interesting happen in that part of Japan during that time period?” And so I sort of stumbled upon it. And then the more research I did into that episode in Japanese history and the characters associated with it, the more fascinated I became.

So the Shimabara Rebellion is one of the very few peasant uprisings against the samurai and the daimyo and the ruling class. And essentially it started with a construction project. It started with Shimabara Castle, with the lord of the Shimabara Province having a vision of building this grand castle for himself. So that’s where it began. And in order to build this monstrosity of a castle, he just kept on increasing the taxes on the people in his domain, and even in the midst of a famine, insisting on higher and higher taxes and prescribing more and more cruel and unusual punishments for those who failed to pay. In addition to that, there was also the element that in Shimabara, being so close to Nagasaki, there were a great many people who were secretly Christian at a time when Christianity was outlawed. So the daimyo of Shimabara, Matsukura Katsuie, was very preoccupied with A) finishing the construction project that his father had begun, and B) rooting out the hidden Christians in his territory. Partly because he was under scrutiny from the Shogun, who was sort of giving him the side-eye, saying, “Why do you need this huge castle? Japan has been unified. There is one Shogun to whom everyone owes allegiance. You’re not fighting your neighbors anymore. What do you need this huge castle for? And we’ve heard reports that there are hidden Christians in your domain. Why aren’t you spending your resources to root them out instead of building this big castle for yourself?” So that’s where it came from. And with all of the pressure turned up on the common people of the province, conditions were ripe for a rebellion. All they needed was someone to rally around.

And the person who played that role was this mysterious figure in Japanese history called Amakusa Shiro. A real historical person, but like Robin Hood, so many legends have grown up around him that it’s hard to tell fact from fiction. But the stories say generally that he was the son of a samurai or of a ronin, that at the time of the rebellion he was quite young, only maybe 15 or 16 years old, that he was quite good-looking, and that he had abilities beyond what could be expected of an ordinary mortal. That by the age of four he could already read. That at a time when Bibles or any sort of religious literature was outlawed, he knew the scriptures as if by heart. And even in some cases that he had some kind of magical ability, like either he was very good at sleight of hand or that he could actually perform miracles. So he was the de facto leader of the resistance movement, with the support of several ronin living in the area who had, in many cases, fought under Christian daimyo and were very happy, towards the end of their life, to give their all to one last campaign and strike a blow on the side of the ordinary people against the oppressive ruling class. So that’s where that got started.

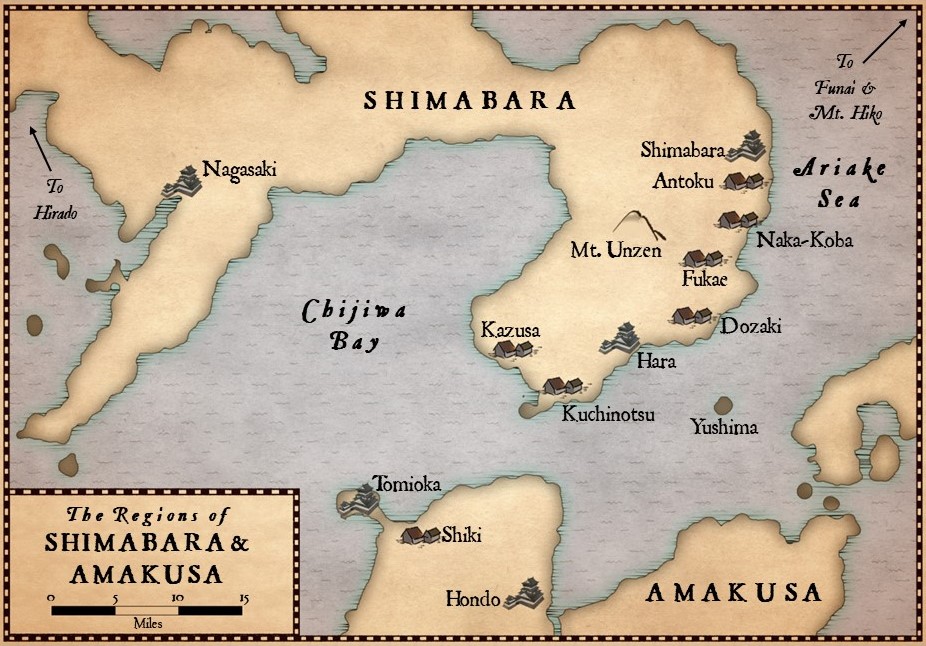

TV: Right, right, right. And of course back then, we didn’t have the prefectures, that it was a completely different layout and all that. But in modern-day Nagasaki Prefecture, is that where this all took place?

CK: That’s right, in modern-day Nagasaki Prefecture. In those days it would have been called the regions of Shimabara and Amakusa, and the proper name that historians use these days, they call it the “Amakusa-Shimabara Uprising.” But “Shimabara Rebellion” is so much easier to say. And “Rebellion” just strikes a note with Star Wars fans.

TV: And then are two castles that are brought up in the book and, and then of course in in actual history, but the Shimabara castle, what ended up happening with that? Did it get fully built?

CK: It did. It’s still there, so you can visit it if you go to Shimabara, it’s now a museum that houses a lot of artifacts that have to do with that time period.

TV: And then the other castle was Hara Castle. Is there anything left of that?

CK: No. You can visit the site of Hara Castle, but very little of the original structure is left standing, just the foundation stones. And unlike many castles in Japan, it hasn’t been rebuilt, I think partly because there are still a lot of bones in that ground that are unidentified, so maybe people are a little wary of building over that. However, again, you can visit the site and – this is kind of cool – you can download an app, and then wherever you’re standing on the site, just look at your smartphone screen and see a virtual reality reconstruction of what the castle would have looked like at the time from your vantage point.

TV: Oh, that’s cool. And, maybe this isn’t a huge plot point, but there’s, let’s just say like a little monster under the castle in the book. You didn’t see that, right? I assume when you visited, you didn’t see the monster, right?

CK: [Laughter] No, I didn’t, but someone in the Edo period apparently had heard of it, because it’s written in a book.

TV: Gotcha. OK, so it did have this reputation of being haunted or something like that?

CK: I don’t know whether the castle itself had that reputation, but a novel of the period that had to do with the Shimabara rebellion did mention that monster.

TV: OK, very cool. It sounds like you went to the whole area and did research and got in touch with the local museums and all that? What was that process like?

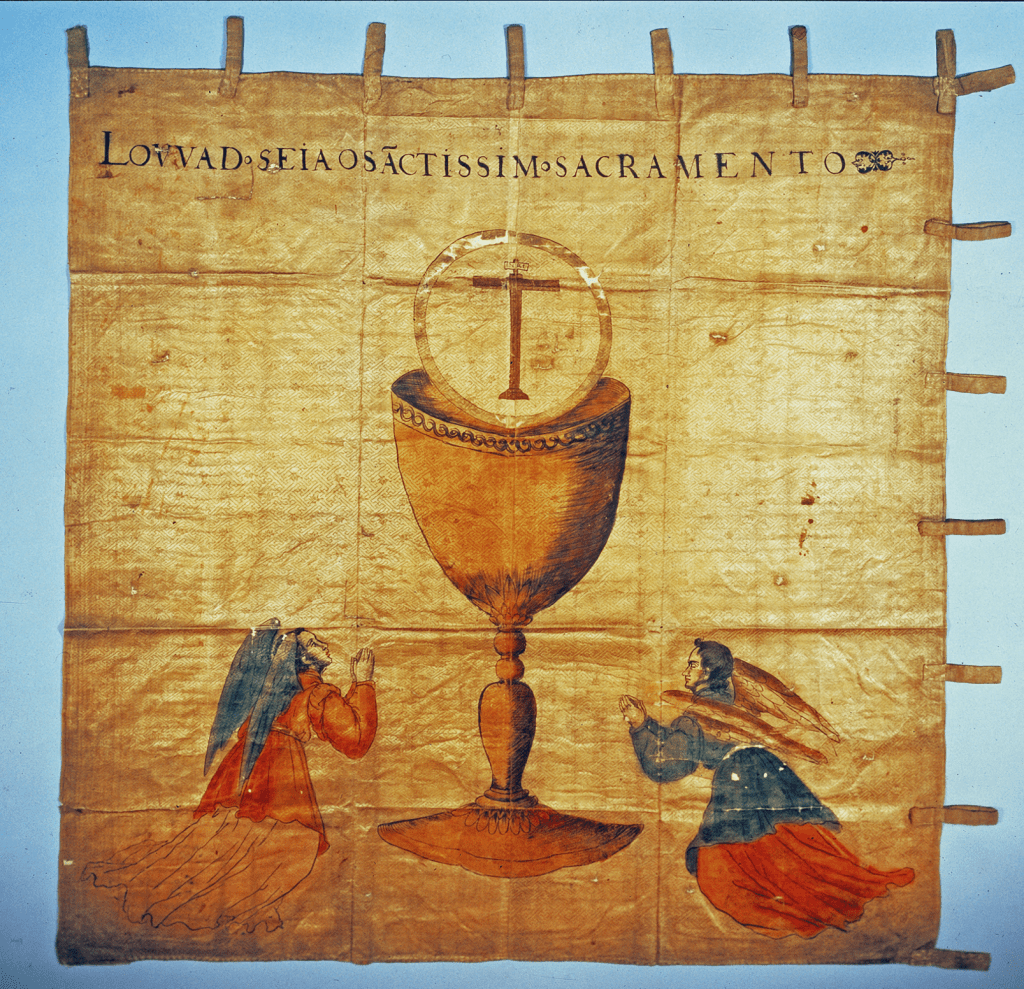

CK: Well, that was a bit of an adventure in itself, just going around all of the museums in the area. And particularly when I went to a certain museum in Hondo and I told them I was writing a book about the Shimabara Rebellion, the receptionist says, “Well, today is your lucky day, because we have Amakusa Shiro’s original battle flag. And usually we don’t display it, usually what we have on display is a replica, but at certain times we actually display the original artifact, and this just happens to be one of those times.” Wow, so I actually get to be in this room with this artifact that Amakusa Shiro held with his own hands, that the characters in my book made.

TV: OK, what was like the pattern on it? Or the design? What? What did it look like?

CK: Well, it looked a bit different from what I had imagined. The design itself is painted in western style, in very vivid colors that haven’t really faded in 400 years. And I looked at the cloth, I just imagined that it would be painted on plain white cloth, but the cloth was fancier than I had envisioned. It was kind of brocade stitched in a pattern. And so, when I was leaving, I spoke to this older gentleman in coveralls and just wondered aloud, “Well, I wonder what kind of cloth that is, what kind of pattern it is.” And he said, “Just a moment,” and he disappeared. And he came back with this huge book printed on glossy paper and opened it. It turned out to be a catalog of every artifact everywhere in Japan that has anything to do with the Hidden Christians. And he opened it to the very page about the battle flag, and he pointed to the name of the article’s author, and then pointed to himself. So here I was talking to the fellow who had literally written the book about Amakusa Shiro’s battle flag.

TV: Oh, wow. If you ask around, you’re going to the places where these things are. So it’s funny how you can get access to these people, right? I think a lot of these people are probably happy to show you and talk to you about all these things that maybe your average Japanese person doesn’t take too much of an interest in, right?

CK: Yeah. And of course, the museum staff and particularly the museum curators who have dedicated their lives to studying this stuff, when they have someone come their way who is showing a genuine interest, of course, they love to open up. And they’re just fountains of information.

TV: Another setting in the book is Dejima, this famous artificial island off the coast of Nagasaki. I assume you must have done research and gone to that area as well?

CK: That’s right. Dejima is still there, or at least a reconstruction of it. At the time it was an artificial island built in the sea and connected to the mainland by a bridge. Nagasaki has grown up around it, mostly on reclaimed land. So now it’s still an island, but it’s an island surrounded by canals in the middle of the city. Like you stand on it, you look over the fence and you can see you’re surrounded by skyscrapers on all sides. But the Dejima historic site is as accurate as they could make it, a reconstruction of what it would have been like at the time.

TV: I’ve actually been to Nagasaki a couple times, but I’ve never had the chance to go to Dejima. Can anybody just go at any time? Are there museums? What is there to see there?

CK: Yeah, there are museums. It’s a reconstruction of the buildings that were there at the time when Dejima was essentially the home to traders, mostly from Holland, occasionally sailors from other European countries who had come there aboard Dutch ships. You can visit the house of the chief of the trading post, you can visit the warehouses, they have dioramas showing what life was like at the time, and artifacts, drawings, videos, all sorts of things.

TV: OK, I’m sure I’ll be back in Nagasaki at some point again, so I’ll have to check it out. But of course, just for anybody unaware, Nagasaki, Dejima was this big trading area, right? But especially once we entered the Edo period, they shut down the country so that nobody can come in. But the Dutch were still kind of barely there, right?

CK: Right. Nagasaki was at that time one of two areas, the other being Hirado, where Dutch traders were allowed. On very rare occasions, they could leave the area under escort, but otherwise they were confined to their enclaves.

TV: In the book, we do have a quick visit to Dejima, and also a Dutch trader, and so there’s a lot of history here in the book that’s super interesting and really gets you curious to learn more. But then, aside from the actual real world history, you also have a lot of the supernatural stuff. Is there any specific ghost or yokai that you were particularly eager to include in this book that you didn’t get to include in the first one, or any one that you particularly enjoyed writing about or researching?

CK: Yes, the one that I was particularly anxious to include was the Gashadokuro, the giant skeleton. Anyone who takes any interest in Japanese yokai at all has probably seen the Utagawa print of the samurai battling this giant skeleton. In fact, well, your listeners can’t see it, but I’m wearing that T-shirt right now.

TV: [Laughter] Oh, nice!

CK: And so, and according to Yokai lore, that’s a monster that appears on battlefields or other places where a number of people have died without a proper burial. So it’s composed of their bones and their spirit of envy towards the living. It’s a giant monster composed of the bones of the unquiet dead. I wanted to make sure to include that. But looking closely at the Utagawa print, you can see there are three figures. There’s this giant skeleton, there’s the samurai fighting it, and then there’s this third figure, the woman who is controlling it. And so that led me down another rabbit hole. OK, who is this woman? What’s her story? And that led me into the legend of Takiyasha Hime.

TV: Yeah, that’s not a legend that I was familiar with. So, when that character came up in the book, that was all new to me. Could you tell us a little bit about her and her story?

CK: Yes. She lived about a thousand years ago, which means that starting from Simon Grey’s time, it would have been about 600 years ago, during the Heian Period. And her father is the historical figure Taira no Masakado, who led a rebellion against the Heian court. His rebellion was crushed and he was sentenced to death. And there are various versions of the story, that when he was executed and his family was purged, she, and in some versions her brother, escaped, and she took refuge in a Buddhist temple and became a nun. And then, one way or another, she acquired supernatural powers. Either she went to a shrine and prayed for 21 days, or else she encountered a wizard who gave her a scroll that gave her magical powers. But either way, she became a powerful witch with the ability to summon various types of yokai. Including, in this version, the giant skeleton.

TV: You just used the word “witch” there. I think the way that you wove that into the story and with the conflict with the Christians, I thought that all worked out really nicely. Like I said, something I really appreciate about the book is the way you wove all these things, like the history and, and the supernatural. In a way that when you scratch beyond the surface, you go like, “Oh, this is actually based on this, and it all kind of works together really nicely.” So again, I really enjoyed that.

CK: Well, thank you. Yeah, it was my intention in writing the book. Come for the yokai lore and stay for the history.

TV: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. For example, like the tengu, right? Like the tengu appears, but it’s not just like, “Hey, I’m a tengu! I’m here! Look at me!” It’s an important part of the story that you wove into it in a good way that pushes it forward, and then it all pays off. So, anything that you can tell us about the tengu aspect like that? Any interesting research that you did for that, or any stories that you discovered while doing that?

CK: Oh, yes. In order for Simon to meet the tengu, first he has to go to this temple run by the sect known as Shugendo, an actual religious sect which is still practiced in Japan today, sort of a mixture of Shinto and Buddhism, and they perform their ascetics usually in the high mountains. Their belief is the mountains are the belly of Buddha. You go into the mountains to leave behind the cares of this world and put yourself in touch with a supernatural world. And I actually joined some shugenja for a retreat on Mount Takao, which is near Tokyo. So basically, a two-day retreat where you learn the basics of Shugendo. The fire walking bit and the meditating under waterfalls bit that Simon goes through, well, those come from personal experience.

TV: [Laughter] Oh, yeah? How was it?

CK: Well, I will say that my instructor was not quite as mean as Simon’s. [Laughter] But he did sort of give me the inspiration, because the one who was leading the waterfall meditation, he looked and sounded kind of like a Marine drill instructor, calling out the mantras: “Namu Daisho Fudo Myo-o! I CAN’T HEAR YOU!”

TV: [Laughter] Oh, I love that! How long did you do that? Like, was that like a weekend thing?

CK: Yeah, it was a weekend thing. So really, barely enough to scratch the surface.

TV: But you maybe you got the general idea, I guess.

CK: Yeah. I also had some illuminating conversations with the Shugendo practitioners I met because I sort of asked them half-jokingly whether anyone had seen the tengu. They all said, well, not personally, but they do believe that tengu were real in the same way that a devout Christian might believe that angels are real, that they are messengers of the gods. And when I asked one person that question, he said, “Well, it’s funny you should ask, because there is a certain story that one of the founders of the Shugendo sect went into the mountains to perform the goma ritual, which involves taking prayers that are written on wooden sticks and making a huge bonfire. And after performing that for several days, he saw a long-nosed inin.” So the inin is written with the Japanese characters for “different” and “person,” so ordinarily it’s meant to mean something that’s not human. So the story is interpreted to mean that he saw a real live tengu. However, you could also read those two kanji characters as ijin, which back in the Edo period was the word for “foreigner,” what a modern would call gaijin. So you could interpret that story in two ways. Either he saw “a long-nosed thing that was not human” or he saw “a long-nosed person from a different country.” So I came away from that conversation thinking, “Well, I went up Mount Takao to look for tengu…but maybe I am the tengu.”

TV: [Laughter] Yeah, exactly! Like especially when you see like the old depictions of white foreigners in Japan, like we’re talking like Edo period and all that, they look rather tengu-ish.

CK: Yes, and so, early on in the book, when they’re talking about a type of creature that has a nose like a tengu and a head like a kappa and wings like bats. So of course, at first Simon thinks that this is some kind of yokai he hasn’t encountered yet. But then he learns that the description is of a Catholic priest. Which is based on actual descriptions from the period, and you can see how they got there.

TV: Yeah, I could totally see that. I love the…so, for anybody that’s not aware, the Christian words in Japanese are based on the Portuguese and I guess the Latin, right? So they’re all romanized to sound the closest they could at the time to the Latin original. So for us English speakers, when you go and you start to learn these words, you go like, why is Jesus “Yes,” right? They say “Iesu,” because it was originally from the Latin and all that. So it’s very confusing for a person that’s coming at it from the English speaker mentality. And Simon is in that situation, like, what is this? He starts to figure out, “Oh, okay, I can see how Padre would become this or whatever.” It’s like, “I’ve been there, I’ve experienced that.” [Laughter] Yeah, yeah, yeah, that’s really funny.

CK: And trying to understand…basically the hidden Christian community of Japan spoke a language unto itself, because originally they had learned their prayers in Latin and/or Portuguese, and then for hundreds of years they were cut off from any contact with the outside world. So there were no priests coming in who could share the original texts with them, and they could never be written down. So they were transmitted orally from generation to generation. And by the time of the Meiji Restoration, where the ban on Christianity was lifted and they could practice freely again, it had mutated beyond all recognition. But there’s one sort of apocryphal story that’s told of one of the ships that arrived in Japan after Commodore Perry, after the national period of isolation was ended. And it had a priest aboard, and when he came ashore, a really old woman rushed up to him with a really excited expression and said, “Abe Maruya Hayashibena.” And he couldn’t really understand, so he called his interpreters like, “What is this? Is this some dialect of Japanese I’ve never heard before?” And nobody could make any sense of what she was saying until they finally realized that she was trying to recite the Catholic prayer, Ave Maria gratia plena.

TV: OK, I got the “Ave Maria” part, but I didn’t figure out the “gratia plena” part. Okay. Very interesting. I mean, centuries in hiding, and then of course there’s also the other Mary-like Buddhist type statues, right? That they tried to hide it in a sense. This is like, no, this is a Buddhist statue, but it’s actually supposed to be Mary, right? All these different ways in which the hidden Christians were still able to gather and practice without being caught and killed, right?

CK: Right, yes. So you see, in those museums, a lot of statues that are supposedly statues of Kannon-sama, and so if anybody questioned them they could say, “Oh, yes, it’s Kannon-sama,” but actually they are a Madonna and child. And other things like the zeni-botoke, a cross that’s made of coins. People would gather around a cross made of coins, so if they heard the officials coming, they could just easily sweep it off the table and destroy the evidence.

TV: Interesting. Zeni meaning “money” and then hotoke meaning “Buddha,” right?

CK: Right. It’s a mystery why they chose that word. But maybe just to avoid arousing suspicion.

TV: Yeah. I mean, not that I know, but that’s just my assumption. Very interesting. I think I’ve been to the museum in Nagasaki. Right? I think there’s one about the hidden Christians, right, in Nagasaki?

CK: There are several in Nagasaki prefecture.

TV: I’m pretty sure I’ve been to one. It’s probably been almost 20 years since I went, so I can’t really remember but it’s a really, really interesting history. So if somebody’s going to Nagasaki, is there a specific place you go, like you should check this out, that you want to recommend?

CK: I would recommend that people go online. If they’re interested in the history of the hidden Christians, there’s a lot of material there. There is a museum in Hirado that’s partially dedicated to it, which I myself didn’t have time to visit, because I was of course primarily interested in the Shimabara Rebellion which was at the very beginning of the age of the Hidden Christians, but from there it went on for 250 years. There are a number of sites in Nagasaki, particularly along the Japan Sea coast, that are associated with them, so I would say, go online. The Hidden Christian community maintains a website where you can see all of the sites that are associated with them.

TV: Awesome, awesome. OK, So yeah, for anybody interested, check that out. But of course, you know, the book comes out this month. I mean, there’s the yokai supernatural kind of spooky aspect. There’s a history aspect. You know, great for Halloween, but I think great for anytime. But it’s also just a really easy to read book. It’s really well paced, so you can get through it really fast. It just keeps on pumping, pumping, the story doesn’t stop. It’s a fun read. And then of course, there’s the first book too, which if you haven’t read, you can check that out. It’s gonna be available on Amazon. The book is called Simon Grey and the Curse of the Dragon God. And do you have a website or anywhere that that people can follow you?

CK: Yes, simongreybooks.com. That will give you links to places where you can buy the books and it will also give you links to Simon’s Log, which tells you a little bit more of the back story and the behind-the-scenes story of how this book came to be.

TV: Awesome, awesome. And there is a third book in the works, correct?

CK: There is indeed.

TV: All right, Well, I am looking forward to that, because the second one ends in a satisfying way, but it leaves you wanting more at the same time. So now that I’ve read the two, it’s like, “Alright, well, give me the third one!” [Laughter]

CK: I promise you, you will not have to wait five years for the third. It’s in the works right now.

TV: [Laughter] Otherwise, I’ll just go down to see Otohime for like a week – no, for like a couple of hours. Then I’ll come back and you’ll give me the third book!

CK: [Laughter] OK, sure.

TV: Alright, awesome. Thank you, Charles. Awesome book, guys, check it out. It’s a fun read. And we’ll talk again when the third one comes out.

CK: Thank you very much, Tony.